Recent Posts

Jump to Technical Commentary

Advertisers, beware: The DV Fraud Lab has discovered a new fraud scheme lurking on customers’ mobile devices. It uses innocent-seeming iOS gaming apps to charge advertisers for phony ad impressions.

Operated by independent cybercriminals using a shared framework called UniSkyWalking, the scheme, which our Fraud Lab has dubbed SkyWalk, is sophisticated, coordinated and very difficult to detect. Our researchers discovered it after noticing a number of apps with abnormally high impression rates and unreasonable click behavior.

SkyWalk fraudsters have embedded secret web browsers inside various iOS gaming apps. These apps are downloadable in the App Store and appear legitimate. Their games are playable.

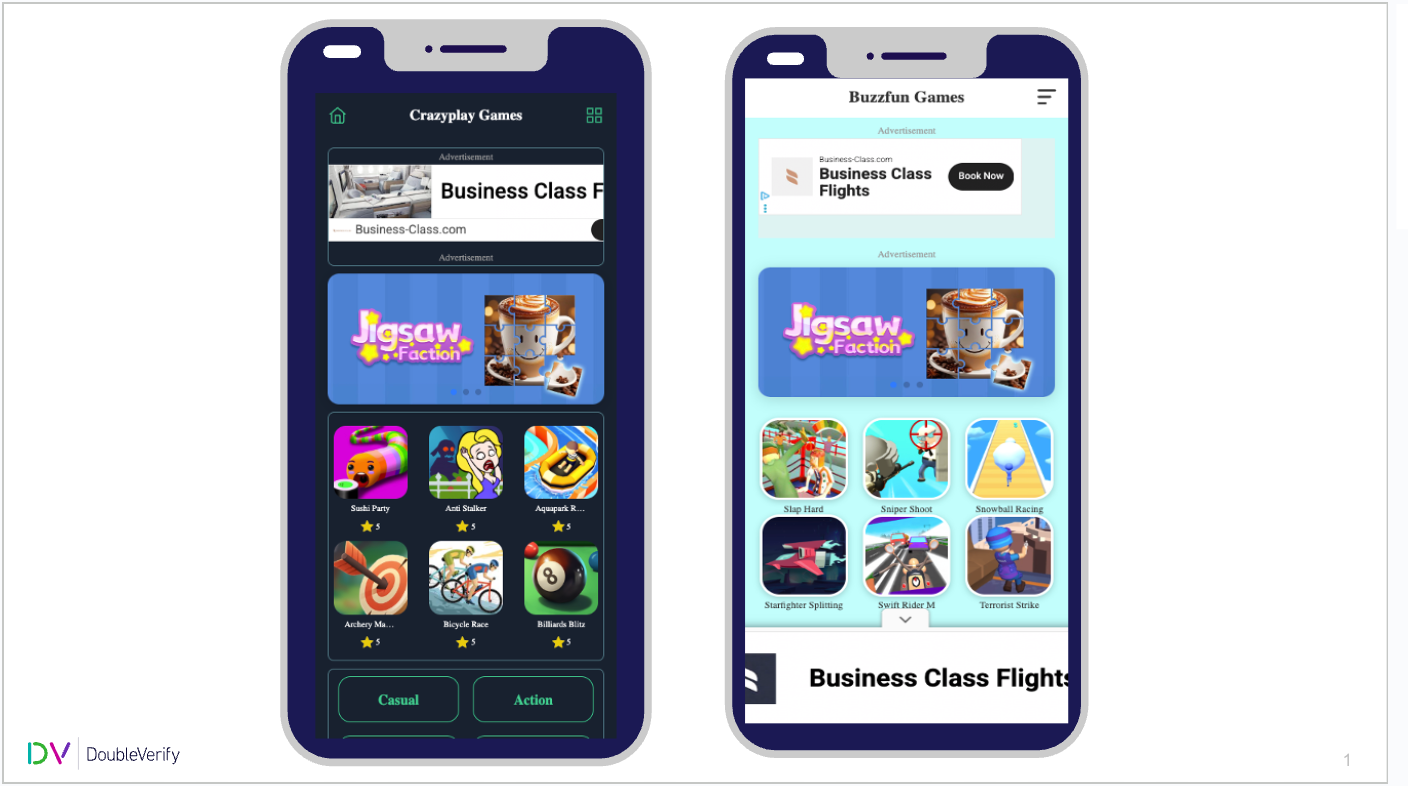

But when a user opens one, the app also secretly launches hidden websites on the user’s iOS device. As the user plays “Sushi Party” or “Bicycle Race” in the app, the hidden sites run in the background, undetected, serving ads no one sees.

Impressions are reported. Advertisers get billed. Not a single ad is viewed by a human.

DV has reported a surge in AI-powered ad fraud this year, including a spike in malicious apps. On iOS, the average volume of fraudulent apps DV identified during the first three quarters of 2025 is over three times that of the previous five years.

Even so, SkyWalk is a standout. It involves dozens of fraudulent apps concealing over 80 fake gaming websites that generate millions of manipulated ad impressions. It employs hidden browser technology to render its websites completely invisible to users and uses touch hijacking to generate premium ad formats. Profit sharing is coordinated among multiple fraud participants.

The SkyWalk fraudsters use AI-generated content to make their fake websites appear legitimate during audits, even though the sites receive no organic traffic. And in auction data, the scheme misrepresents mobile app traffic as website traffic to evade Open Measurement SDK, the industry-standard detection tool that monitors in-app ads but not browser-based ads.

SkyWalk impacts marketers by wasting ad spend while delivering no brand awareness. It inflates performance metrics, which can skew campaign optimization efforts.

Consumers, too, are unwitting victims. While they play games on these malicious apps, the hidden websites running in the background are draining their devices’ battery power, processing power and memory. Their devices can even overheat.

Standard measurement tools aren't enough to catch SkyWalk. Marketers should seek out advanced fraud detection from verification providers with the technical expertise to perform sophisticated analysis. Continuous monitoring is also critical, as fraud networks evolve and new schemes emerge.

Contact a DV representative.

Learn more about protecting your campaigns with DV.

By Nir Danon, Cyber Researcher, DV

In early 2025, a few mobile apps caught the attention of DV researchers. “We noticed abnormal impression rates, not served within operationally reasonable parameters,” said DV Fraud Research Manager Arseny Levin. “When we investigated these apps, we found that they fired impressions even before finishing the tutorial splash screen, when no ads were visible to the user.” Further investigation revealed that these impressions were categorized in auction data as web ads, not as mobile app ads. This pattern of misrepresentation often signals sophisticated fraud.

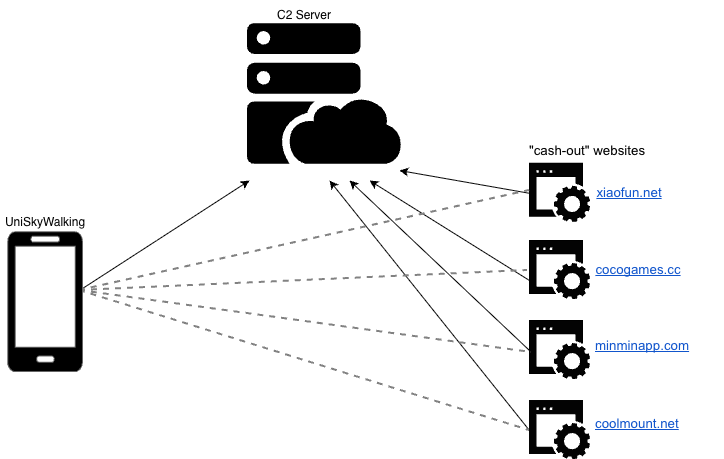

Additional analysis of the network activity of these apps revealed communication with a C2 (command-and-control) server used to retrieve JS scripts, configurations, and lists of websites. These credentials were then woven into the fraud scheme.

An in-depth analysis of the apps revealed a framework through which they load “cashout” websites in the background while a user engages with the mobile game. The app developer then profits from impressions no user has viewed.

Websites used in this fraud scheme include:

SkyWalk is especially sophisticated, as it evades normal viewability-measurement tools. It circumvents Open Measurement SDK, which measures in-app impressions, by serving ads through a web browser.

The scheme operates as a coordinated network with a revenue-sharing structure, rather than as isolated cases. Each actor carries an identifier from the app to the C2 server and to the websites to systematically track and distribute fraudulent profits among participants.

The shared framework found in each of the apps investigated, called UniSkyWalking, is responsible for the practical part of the scheme. It holds a pool of WKWebView objects and handles hiding the WebViews, refreshing the URLs of the websites loaded via WebView, injecting JS scripts into those websites to avoid interfering with the game being played, and retrieving information about the ads running in the WebViews.

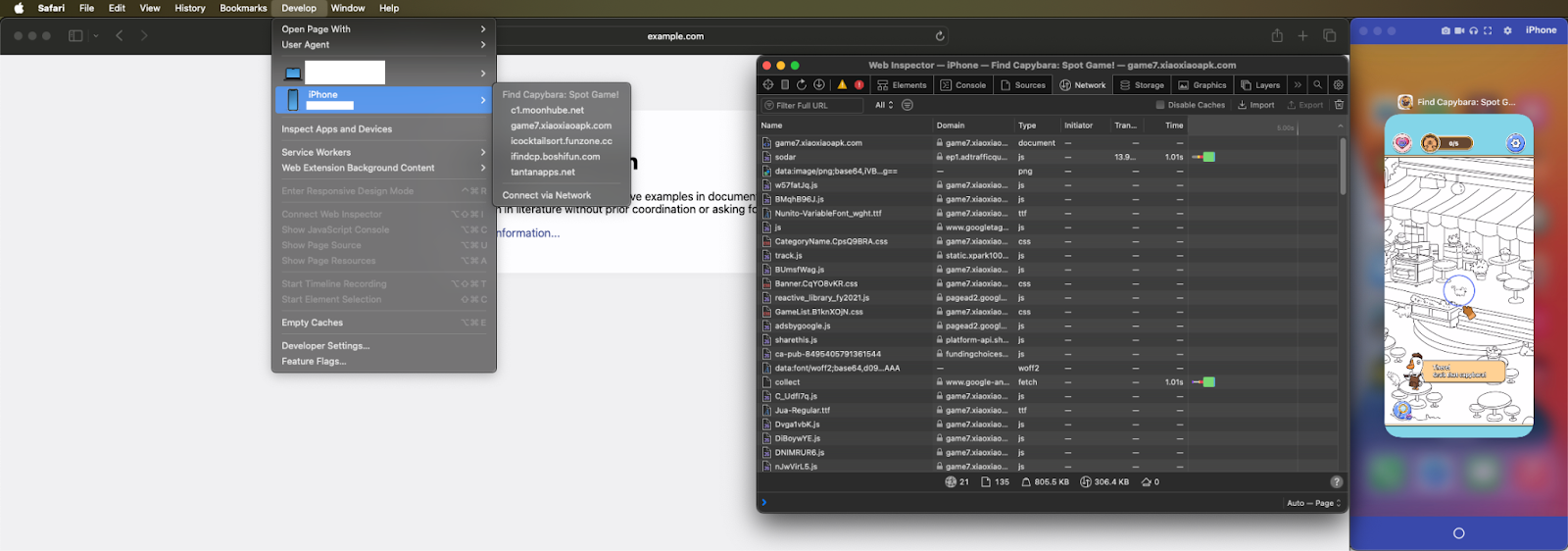

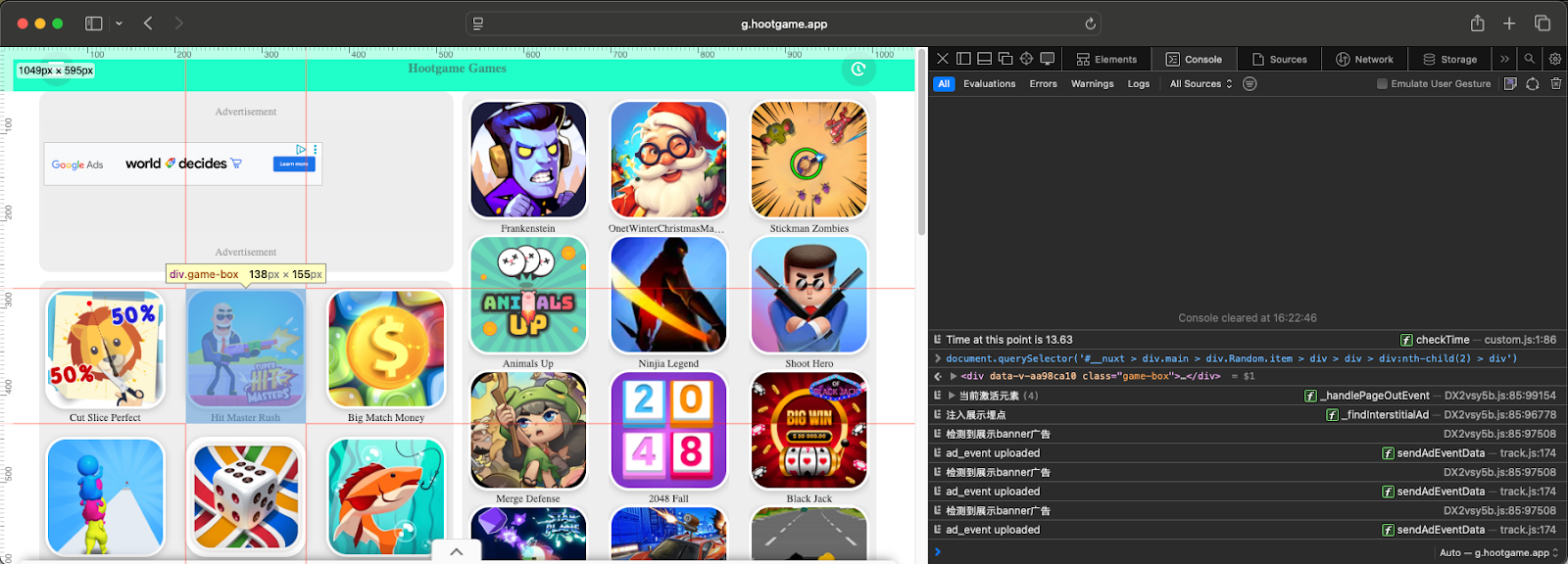

To load the cashout websites without giving the user any visual indication, UniSkyWalking uses native methods of hiding and stacking WebViews. This behavior can be observed by running those WebViews in debug mode using Safari Web Inspector:

By analyzing this framework, DV researchers uncovered the scheme’s evasion mechanism. As seen at the right side of the screenshot (the researcher’s emulated environment), the mobile game is still in the “tutorial” stage, no other app is open, and no website is displayed to the user. However, calls to websites are being recorded, proving that websites are loading in hidden WebViews. The network logs show a website placing requests and reporting fake impressions.

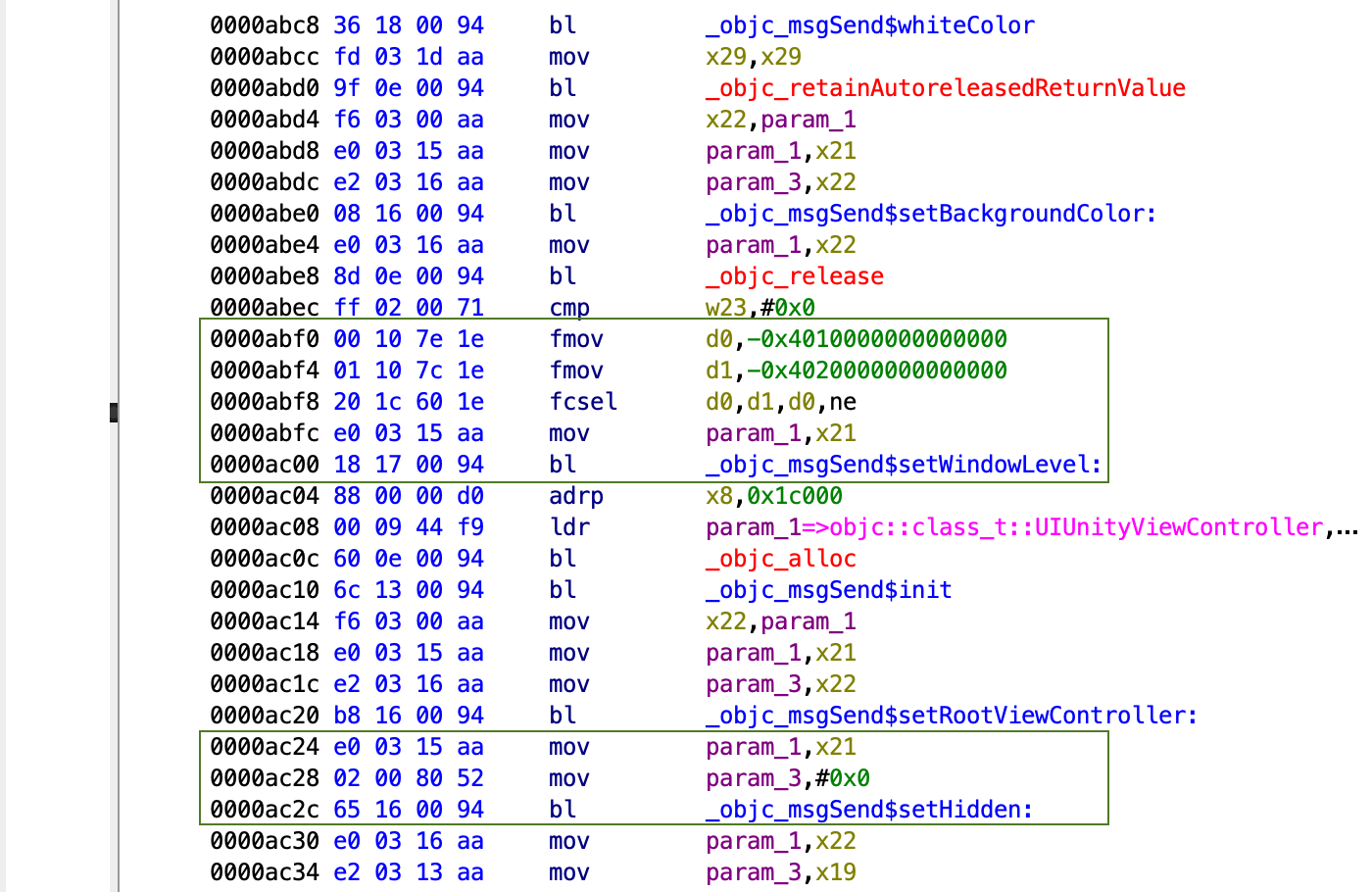

By following the flow of the CreateWebview() function, DV researchers identified the sequential API calls responsible for hiding these WebViews through a layered UIWIndows concealment strategy and other manipulation tactics.

The following screenshot highlights the fraudulent sequential API calls:

The framework achieves the visual effect by coloring the background white using setBackgroundColor, setting UIWindow levels to negative values (to avoid passing the human user’s interaction with the window to the hidden layered WebViews) using setWindowLevel, and ensuring that the WebViews truly are hidden using setHidden.

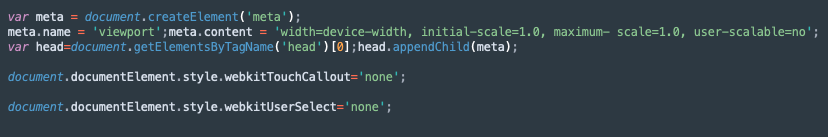

Dynamic analysis revealed the JS code injected into those hidden WebViews. The code shown below appears as embedded strings in the framework’s binary. The code masks various user gestures that might interact with the hidden WebViews and reveal them to the user playing the game.

The first JS code sets the viewport to the device's dimensions, sets the zoom to 100% and disables zoom to handle the pinch gesture. The second JS code disables the long-press gesture on WKWebview, which usually causes a context menu to pop. The third JS code handles the long-press + drag gesture normally used to select text inside a browser environment on mobile devices.

This JS code injection to the WebViews, combined with the layering and hiding of the UIWindows, is extremely effective. Paired with other native methods of hiding, such as setting different WKWebViews properties, the JS injection makes the WebViews almost undetectable to the end users.

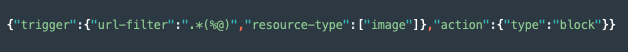

In the configIGnoreImagesWithImagesUrlContainStrings function, a content-rule blocks cashout websites from loading images — which are unnecessary, since these ads don’t appear to users. Loading them could also raise suspicion if users noticed their data plan draining very quickly.

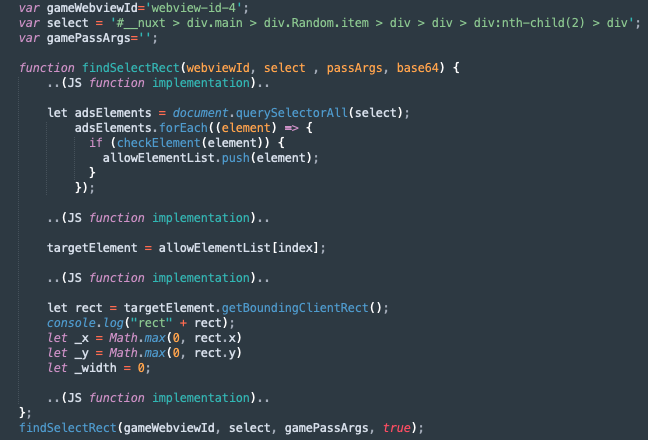

In additional findings, encrypted data delivered from the C2 is JavaScript code, along with CSS query selectors retrieved as part of the configuration from the remote server:

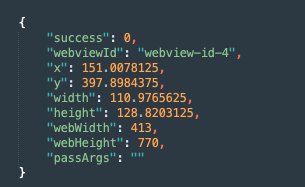

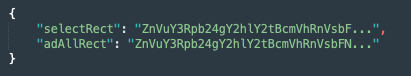

Its output (on an actual device):

The SimulateTouch() function exported by this framework allows JS scripts to run inside the WebViews. Another utility function helps make the translation between the JS layer coordinates and the actual windows. The framework implements touch hijacking in the hidden window that contains the WebView: It listens to all TouchEvents and triggers a UITouch with the patched X,Y coordinates scaled to the actual screen of the device.

Why go through all this manipulation? To boost profits. A click in the right place on a webpage triggers a Google vignette, a full-screen ad that appears immediately after a user engagement. Because this type of ad likely gets the user’s full attention, its CPM is higher than that of a simple banner.

The cashout site below (shown in a PC browser) looks like a typical HTML5 gaming website. But running the CSS query selector from the C2 server reveals that it points to an ad trigger.

Nearly any click or interaction within the game options will deliver a vignette ad. The user will remain unaware of this, because their clicks are loading hidden URLs. All the user sees is a low quality mobile game, with possibly some odd glitches or delays. Advertiser dollars will be spent in vain, lost to this hijacking scheme.

How does the cashout site synchronize so well with the framework? Where do the cashout sites come from? And what about the query selector matching those websites?

The main fraud operation is coordinated through a remote web server with several subdomains. The server uses different endpoints for the different “affiliate partners” who implement the fraudulent framework in their apps. It’s similar to the way an ad SDK is implemented in an application and communicates with its ad servers.

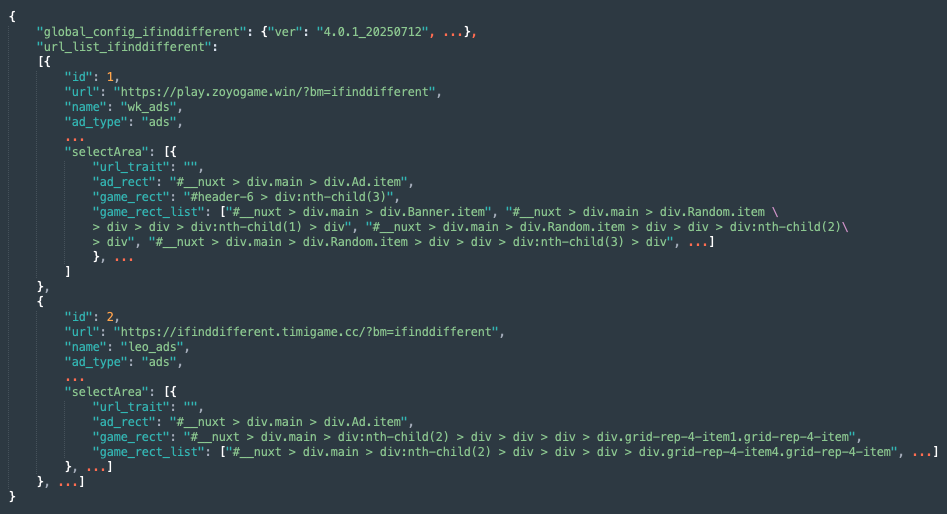

The C2 server uses the bundle identifier of the apps as well as a unique identifier of its own. The following example shows a decrypted, minified version of the response from the endpoint:

Although this looks complex, it is quite straightforward. The C2 server provides a list of URLs that the app com.minigame.SpotTheDifference (referenced as “ifinddifferent” in the fraud operation) can iterate to generate false ad impressions. It also provides the query selector used to initiate vignette impressions.

Another global endpoint used by all applications in this fraud operation,

/common/script-v2.json, delivers the following encoded data:

After decoding this information, we found it to be the same JS code the SkyWalk framework uses to get the X,Y coordinates (findSelectRect function) noted during our dynamic analysis of the applications — without the needed parameters the SkyWalk framework provides during runtime.

To tie it all together: The C2 server provides configuration JSON files and JS code to the various applications that have implemented the fraud framework. Using the framework, the apps then load the websites in the invisible WebView and run the JS given to them. Using the results from the JS code, the apps use touch hijacking to interact with the cashout sites.

The cashout webpages themselves are the most innocent-seeming link in the chain. Sold to advertisers as inventory, they appear to be free of malicious code. To a random visitor or an auditor, they look like harmless, high-traffic gaming websites. However, they get very little organic traffic. The majority of impressions originating from them come from hidden iOS WebViews.

Although they have different titles and domains, these sites appear to be templated, with similar design, page layout structure and categories. They usually host the same HTML5 games which, unlike AI blog and “news” site content, can be deployed once and require little maintenance.

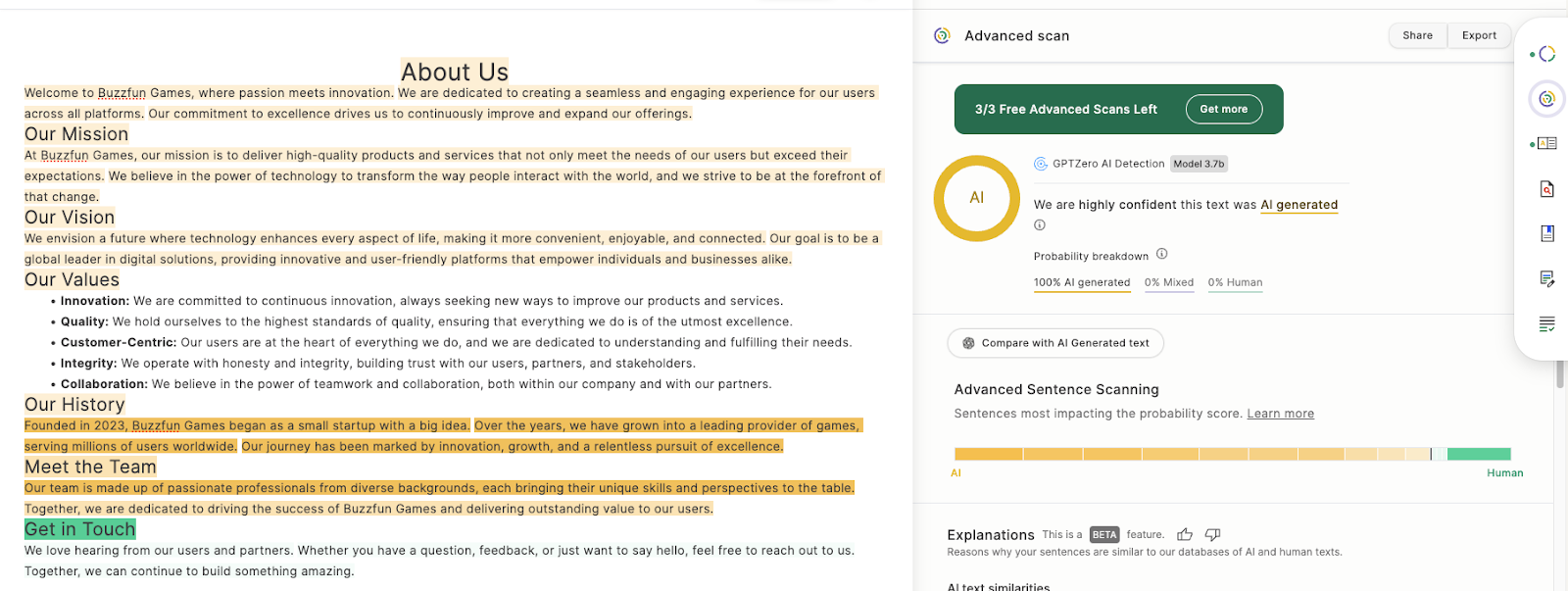

A closer look at their About Us pages reveals that these websites all use the same text. DV’s proprietary AI content detection models and public AI content tools found that this text was created with GenAI.

These cashout websites use the same unique identifiers seen in the SkyWalk framework and the C2 server to link website impressions to the apps running the sites in the background.

For example, in their hidden WebViews, the bundle com.fantasy.jigsaw loads the URL https://game9[.]shenapk[.]com/?bm=ijigsawty with the unique identifier “ijigsawty,” and the bundle com.zoola.watersort loads the URL https://game9[.]shenapk[.]com/?bm=iwatersort with the unique identifier “iwatersport.”

The “bm” parameter allows for differentiating the apps and affiliates using the cashout website, and for distributing profits according to each app’s contribution.

Finally, each website uses a tracking script requested from the C2 server to report “engagement” events and ad fills to their logging service.

The SkyWalk investigation revealed the common overlap between impression fraud, click fraud and GenAI-powered slop sites. AI slop sites were frequently the cashout vehicle in this scheme. One example, below, is presented as a news website with “Bussiness” [sic] and “Investment” sections. In fact, it is largely a warehouse of generic AI slop content shared with additional sites tied to the SkyWalk scheme:

The DV Fraud Lab continues to identify mobile fraud and protect DV clients from its consequences, including click-hijacking schemes such as SkyWalk. In 2025, the DV Fraud Lab has uncovered nearly 9,000 fraudulent mobile apps, thousands of fraudulent CTV apps and websites, and dozens of bot scheme networks including evasive AI agent schemes.

To learn more about the Fraud Lab’s work or request the list of apps and domains associated with SkyWalk, visit the DV Transparency Center or contact your DV account manager.